Ecological Changes in Coyotes (Canis latrans) in Response to the Ice Age Megafaunal Extinctions

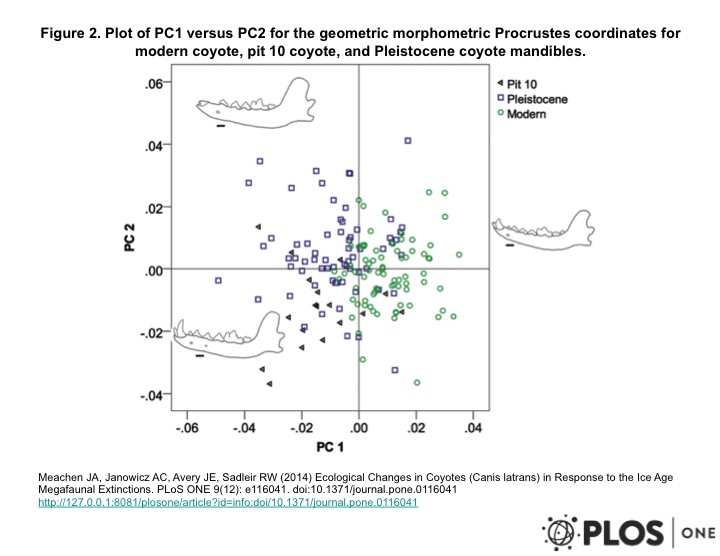

This slide shows changes in the coyote’s mandible over time. Meachen et al.’s study examines samples from three distinct populations: Pleistocene, Holocene (Pit 10), and Modern. Their findings indicate that the coyote was able to adapt to environmental changes by shifting its dietary habits. The Pleistocene coyote mandibles are best suited for hunting large prey; the smaller mandibles of the Holocene and Modern coyotes indicate a shift toward smaller prey and ominvory. It is likely that this adaptation allowed Canis latrans to survive while other mammals went extinct in the late Pleistocene.

Abstract

“Coyotes (Canis latrans) are an important species in human-inhabited areas. They control pests and are the apex predators in many ecosystems. Because of their importance it is imperative to understand how environmental change will affect this species. The end of the Pleistocene Ice Age brought with it many ecological changes for coyotes and here we statistically determine the changes that occurred in coyotes, when these changes occurred, and what the ecological consequences were of these changes. We examined the mandibles of three coyote populations: Pleistocene Rancho La Brean (13–29 Ka), earliest Holocene Rancho La Brean (8–10 Ka), and Recent from North America, using 2D geometric morphometrics to determine the morphological differences among them. Our results show that these three populations were morphologically distinct. The Pleistocene coyotes had an overall robust mandible with an increased shearing arcade and a decreased grinding arcade, adapted for carnivory and killing larger prey; whereas the modern populations show a gracile morphology with a tendency toward omnivory or grinding. The earliest Holocene populations are intermediate in morphology and smallest in size. These findings indicate that a niche shift occurred in coyotes at the Pleistocene/Holocene boundary – from a hunter of large prey to a small prey/more omnivorous animal. Species interactions between Canis were the most likely cause of this transition. This study shows that the Pleistocene extinction event affected species that did not go extinct as well as those that did.”

Copyright: © 2014 Meachen et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.